*See editor’s note at the bottom.

In 2014, trustees with the El Rancho Unified School District–located within the working-class city of Pico Rivera—passed a resolution that made ethnic studies a high school graduation requirement. It became the first district in California to pass such a measure, and came years before Sacramento tried to implement it statewide.

El Rancho hired instructors to teach the courses and rolled out curriculum that emphasized looking at media and literature through a multicultural lens. “We were also insulted and harassed by others who sent vicious emails rebuking our decision and calling us anti-Americans,” board president Aurora Villon told Chapman professor Miguel Zavala in 2016 for UCLA Xchange. “It was difficult to understand why some people were so angry at the thought of having children’s cultural capital acknowledge and recognized.”

Those haters returned with a fury this year. Before letting out for summer break, the district forced Guadalupe Carrasco Cardona, a well-liked Mexican-American studies teacher, to resign her position at Ellen Ochoa Preparatory Academy after just a year. The board also rotated out Principal Elias Vargas, who ultimately resigned instead of accepting his next assignment.

And former supporters of ethnic studies turned on Jose Lara, a trustee who co-authored the 2014 resolution, and won a Social Justice Activist of the Year award in 2015 from the National Education Association for his work.

“Unfortunately, El Rancho feel prey to the Trump effect,” Lara says. He’s referring to a small, but vocal pro-Trump group of detractors both in and outside of Pico Rivera that have hounded the school district this year. “During an election year, it has been enough to rattle the cages of some of my fellow board members. Regardless of the politics, it is important to always do what is best for the students and the El Rancho’s board majority has backtracked on our advances in ethnic studies.”

The focus of the controversy was Carrasco Cardona. Her Mexican-American Studies course surveyed pre-Contact history, colonial Mexico, the U.S. invasion of 1846 and the modern Chicano movement. The class also incorporated writing, literature and arts. “Throughout all of it, there were connections to contemporary themes of immigration,” she says. “Students connected to their own history.”

But a whisper campaign around Carrasco Cardona’s political affiliations almost as soon as she started in 2016. The rumor mill charged that Mexican-American Studies under her helm was becoming a vehicle for “racism” against whites and others, an accusation she vehemently denies.

“It was really quite unnerving,” Carrasco Cardona says. “I did nothing but teach peace, love and critical thinking; curriculum that speaks truth to power.”

Others didn’t see it that way, in criticisms that became public at board meetings around her resignation. “Ethnic studies is about celebrating people, culture and humanity, not about pushing an agenda or raising any one ethnicity over another,” Christina Mata, an ethnic studies lead teacher and district facilitator, is quoted as saying in the Whittier Daily News. “That, my dear friends of the community, is called racism — not ethnic studies.”

Carrasco Cardona also had to fend off claims that she purchased curriculum from Sean Arce, former director of Tucson Unified’s Mexican-American Studies department. The teacher claims that the concerns were rooted in administrators wanting to copyright their own teacher-led curriculum for sale.

“Villon didn’t want anybody else to have any authority or knowhow in the ethnic studies world in her district,” Carrasco Cardona says. “She wanted to be the one in control of it.”

Villon didn’t respond to an interview request for this article.

**

One day this year, Principal Vargas, who Carrasco Cardona holds in high regard, brought the teacher into his office to take a temperature check on the rumors about her. Vargas brought up Arce’s curriculum, which Carrasco found shocking; she didn’t even know if he bothered selling it or not.

Vargas also asked her about Unión del Barrio (UdB) and the Association of Raza Educators (ARE). Formed in 1981, UdB broke with the Committee on Chicano Rights to become a decidedly socialist organization and owes its foundations to San Diego. Spurred by Proposition 187, UdB members later helped form ARE in 1994 to promote critical pedagogy in instruction (full disclosure, my brother is treasurer for the latter organization but doesn’t belong to the former).

Carrasco Cardona doesn’t deny being a member of both groups, but insisted she never brought UdB into her classrooms.

“No parents, no students even knew what those organizations were, much less that I was a member of them, until they started participating in board meetings,” she says.

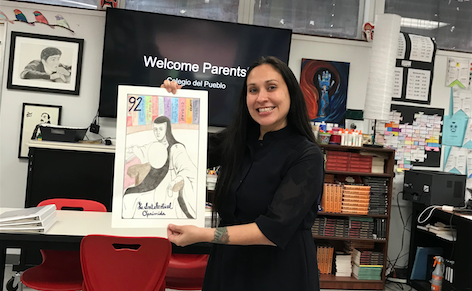

Despite the growing controversy around her, Carrasco Cardona scheduled cultural field trips for students. On a bus ride back from the Los Angeles Theater Center to see Latino plays, parent chaperons inspired a new idea: They wanted to learn what their children learned. A few months later, Carrasco Cardona helped form a nine-week “Colegio del Pueblo” ethnic studies course for parents. They met twice a month at Ellen Ochoa.

“Having this class not only helped me grow closer to my daughter, it really impacted me in a way that was life-changing,” says Leanne Ibarra, whose 14-year-old took Mexican-American Studies.

But Carrasco Cardona’s outreach to parents proved to be the beginning of the end for her.

Villon confronted her about who granted permission for the class at an Ethnic Studies Summit at Cal State Long Beach on Cinco de Mayo. “All of sudden, two classes before it ends, we got the mandate that we had to shut it down,” Carrasco Cardona says.

The teacher expected it given all she’d been through but that didn’t stop the shock felt by parents. “It was devastating,” Ibarra says.

Parents began to attend El Rancho board meetings in support of Carrasco Cardona. “We gave our speeches and strongly urged them to bring the class back,” Ibarra says. “About a week-and-a-half later, we found out she was pushed out.”

But the battle over ethnic studies didn’t end there. A hit piece in the rightwing* Los Cerritos News followed days later, claiming UdB plotted a “communist” takeover of the district through Lara while conveniently lumping him with Gregory Salcido, an El Rancho High School history teacher who made national headlines for filmed comments in the classroom where he referred to members of the military as the “lowest of our low” and “dumb shits.”

Lara actually made the motion to have Salcido fired, but that didn’t make it into the Los Cerritos News story. Instead, it dabbled in Russiaphobia with a crappy photo of a supposed Russian flag hanging from a gym at a school site. Villon took the opportunity to call Lara “ruthless” in a quote blaming him for a social media campaign against her and the ethnic studies program she took credit for.

Meanwhile, Ellen Ochoa students responded to Carrasco Cardona’s resignation by organizing to keep their teacher and Principal Vargas. The board called a special meeting in June but ultimately ignored the student’s wishes.

“If there’s one thing that touches me more than anything else, it is when students are used,” Villon said during the meeting. “We are not a district that advocates racism. We are not a district that dislikes people because they’re white. We are not a district that has an agenda. I cannot discuss what happened at Ellen Ochoa because that’s confidential, that’s a personnel matter. Three of us here don’t have an agenda,” positioning herself against Lara and another trustee.

**

Comments like those inspired Ibarra to run for school board herself. “They all have these fancy titles,” Ibarra says of trustees. “I felt intimidated but the students supported me and told me those titles don’t matter.”

Lara, who’s up for reelection, supports her campaign. “Ibarra represents the best our school district has to offer,” he says. “She is bringing a fresh new voice to the board with a working mother’s perspective that is currently lacking.”

Whether a new majority can be established to bring Carrasco Cardona’s vision of ethnic studies back remains to be seen. Adrian Michael McEachren, a juvenile probation officer who lambasted Carrasco Cardona supporters as being “brainwashed,” is also running for an open seat and is even endorsed by the teacher’s union. Whatever happens to ethnic studies moving forward, Villon won’t be there either way; she decided not to run for reelection.

“If El Rancho Unified is going to be the ‘revolutionaries’ of ethnic studies, then it should stay true to it,” Ibarra says. “We don’t want to water it down.”

*UPDATE, NOV. 13, 2018: In an email sent this morning, Los Cerritos News editor Brian Hews complained that we didn’t link to his story, and took issue with our characterization of his paper as “rightwing,” arguing he is a “dye [sic]-in-the-wool Democrat” and demanded we retract the description, as he alleges it is defamatory to him. We linked to his original story, and regret he does not like our description of his paper.